Season 2: the Winter Edition

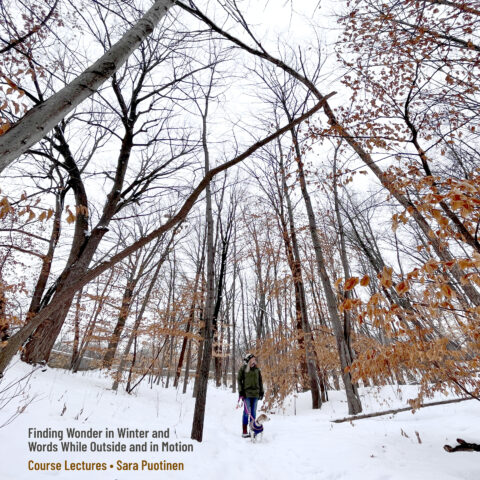

Welcome to Finding Wonder in Winter and the Words While Outside and in Motion! My name is Sara Puotinen. I live in South Minneapolis, four blocks from the Mississippi River Gorge. Six years ago, I started a writing project about running and the experience of training for my first marathon. After I read Thomas Gardner’s Poverty Creek Journal and took an experimental poetry class at the Loft, my project changed: more poetry and more experiments with searching for better words to describe what it feels like to be running beside the gorge.

Transcript Continued

Then, when I was injured and unable to do the marathon, my project grew beyond documenting my training to exploring what it means to be moving while writing and writing while moving, and how both help me to notice a place, the Mississippi River Gorge, and be in wonder of it.

I began learning to notice — my thoughts, my body, a place — and how to slow down. Finding delight. Searching for better words to describe what I think about when I’m running. Building skills to help me navigate the world as I lose my central vision. Devoting more attention to poetry. Discovering how to be in wonder in the midst of a broken world. And, somewhere along the way, through the process of returning day after day, week after week, year after year, to the Mississippi River Gorge to run and notice then write about it, my project became a practice. I developed a regular and ongoing relationship with moving and noticing and writing. Over the years, this relationship has taken many forms and involved a lot of different experiments, but what has held it together is the small, steady structure I consistently follow: I go outside and move. While I’m moving, I try to pay attention. Then, I return home and write about it.

Finding Wonder in Winter and the Words is designed to give you a chance to try out this structure and see how it might work for you through lectures, brief readings, experiments, discussion, and, most importantly, practice. For the next six weeks, you will have the chance to practice this structure on a regular basis — the goal: at least three times a week.

For our structure, we’re building off of Mary Oliver’s suggestion in her poem “Sometimes.” She writes:

Instructions for Living a Life:

Pay Attention.

Be Astonished.

Tell About It.

Our version of Oliver’s instructions will be:

Go outside, move.

Pay attention while moving.

Be open to wonder.

Write about it in a movement log.

This first week of class is about getting started and reflecting on how moving outside in winter can help us notice and be in wonder. I will review the structure and directions for the movement logs and we will think about how to move outside in winter. In week two, we will study several forms of attention to try out while moving. In weeks three, four, and five, we will define wonder and find ways to be in wonder in the winter. I’ll describe three of my favorite winter wonders: the cold (week 3), snow (week 4), and layers — both removing and adding them (week 5). In the final week, we will discuss how the structure did and didn’t work and brainstorm ideas for what to do next with your new practice. Throughout the class, I’ll offer experiments to try that help to translate your wonder into words.

Three elements that are central to this class are: 1. moving through an outside space, 2. developing a habit, a ritual, a practice and 3. using a movement log both to document that practice and as part of the practice.

Moving through outside space

There are many ways in which standing or sitting still outdoors somewhere can help with paying attention and being in wonder. And, moving, then briefly stopping, will be part of some of the experiments you can try. But, for this class, we will focus on moving through outside space and the specific ways it helps us to notice the world and be in wonderment of it — what moving does: to how we think or feel or notice; to words, ideas, our connections to a place; to us, our understandings of self, our breathing, our senses. In moving, it might start with the physical, “the heart pumping faster, circulating more blood and oxygen not just to the muscles but to all the organs—including the brain,” but something beyond the physical often happens: we feel different, more open to the world, more willing to notice and be in wonder of it.

Moving through outside space is important too. It enables us to breathe fresher air and to be out in the world. It also gives us the opportunity to devote time and attention to a place, not only to become more familiar with it — its histories, terrains, inhabitants, but to behold it and care for and about it, to imbue it with meaning and make it sacred.

Winter is a great time to be outside if you want to learn more about a place. Bare trees, less crowds on the paths, better views. Nests normally hidden by leaves now visible, a fox’s movement above the river recorded in the snow. So many secrets revealed! And, moving is a great way to be when outside in winter. How else can you stay warm out there?

Developing a practice

Learning to give attention and be open to, and then in wonderment of, the world are things we need to practice repeatedly. For many of us, it was easier when we were kids and full of curiosity. As adults, it’s harder to slow down, to notice the world and be dazzled by it. We don’t have time. Our attention spans have shortened. We’re discouraged from expressing too much enthusiasm. We’ve been overwhelmed by life — too many obligations, too much suffering. We need to remember and re-learn how to pay attention and be moved — astonished, dazzled, amazed — by what we notice. One way to do this is through practice: dedicated effort on a regular basis. And one way to do this practice is by going outside several times a week and moving, then writing about it, either after returning home or while still outside.

Using a movement log

While outside and in motion, even when we notice things and are in wonderment of them, it’s easy to forget what we noticed, or how we felt while noticing it. A movement log is a great way to document this. Not only does it give you a record that future versions of yourself can look to (I’m constantly thanking past Sara for what she wrote down that I would have otherwise forgotten), but the act of writing it down — sitting somewhere and remembering, thinking through your time outside and putting it into words — becomes part of the practice of giving attention and being in wonder.

Keeping a movement log is a central part of this course. Here are the instructions, which you can also find as a separate document on the resources page:

First, the basics:

At least 3 times a week:

Go outside.

Move (aim for at least 20 minutes).

Pay Attention.

Be open to wonder.

Write about it in your movement log.

Movement logs should include the following:

- Date

- Route/location

- Weather/temperature

- A few sentences on what you did or how you/your body felt as you moved

The rest of the entry will be about paying attention and being in wonder. In addition to a big list of suggestions/prompts/possible experiments, I will offer several activities related to our topic of the week that you can try to help you practice attention and be in wonder.

Try to be consistent in this basic practice. The benefits of a log are in the accumulated effects. It is slow, small, satisfying work. The practice of noticing, then finding wonder and words to express it, builds over time. You not only get better at doing it, but you create an archive of ideas, images, thoughts, experiences, details that you can use in future writing projects and in life.

So, that’s it. Remember: the overall goal of this class is to give you the time and space to experiment with a new practice. Some things might work, others might not. This is your opportunity to have fun, to experiment, to share strategies and be inspired by each other, and to see what might happen when you go outside and move, pay attention, be in wonder, then write about it on a regular basis.

Getting Outside and Moving: Some Reasons

from Have You Ever Tried to Enter the Long Black Branches/ Mary Oliver

Who can open the door who does not reach for the latch?

Who can travel the miles who does not put one foot

in front of the other, all attentive to what presents itself

continually?

Who will behold the inner chamber who has not observed

with admiration, even with rapture, the outer stone?

Well, there is time left —

fields everywhere invite you into them.

And who will care, who will chide you if you wander away

from wherever you are, to look for your soul?

Quickly, then, get up, put on your coat, leave your desk!

Stepping away from a desk, getting up from a chair, heading out to a trail, can help us untangle knots in our thoughts, work through difficult ideas, find better words. It can open us up, slow us down, transform our thinking, enable us to get to know a place, inspire us, provide us with details, images, experiences for our work. And, it can help us to not only endure winter, but to celebrate it.

In an article titled, “The Magic of Winter Running,” Jonathan Beverly proposes:

As we enter this December, we can hunker down to endure a dark winter, or we can head out and see familiar paths with new eyes. As we taste the crisp, fresh air and float through the white quiet we may feel a spark of long-forgotten magic, and maybe even hope; hope for a different spring, one we’ll be ready to embrace with the youthful strength of a winter well lived (The Magic of Winter Running/ Jonathan Beverly).

Here are a few reasons I’ve come up with for why Moving Outside in the Winter is Magical:

- Fresh air! Open spaces! More room to breathe and to be!

- You use your body and work on your relationship with it, find new ways to make it part of your writing

- Gets you up from your chair, out of the forced, stale air, and away from the same four walls you see too much of on the coldest days of winter

- Clears your head, restores your mind, unclenches your jaw

- You get to be with the birds, smell the cold, feel the soft snow under your feet, hear the different ways it crunches, see your breath

- A chance to encounter something delightful or ridiculous or strange, to collect a new image or story, to experiment, to be with the river

- Learn more about your neighborhood — the people or the dogs or the terrain

- Helps you work through a problem — in your writing, life

- Helps you forget some things, remember others

- The possibility of syncing your brain with your feet and the world

Winter activities to try

Even with the cold, the snow, the icy paths, there are many ways to get outside and move in the winter. You can pick one and stick with it for your practice — I mostly run — or you can mix it up with different activities. It can be fun to experiment with a range of winter activities to see how they affect your attention differently. What do you notice when you’re shoveling that you don’t when you’re sledding, or vice versa? How do you hear differently when you’re walking versus when you’re skiing? What does the river look like while you’re hiking? running? show-shoeing?

To inspire you, here are a few words describing ways to move in the winter:

Running:

I’ll begin with running because it is through running that I realized how much I love moving outside in the winter — but, not for long, an hour or less in 0 degrees is enough for me! Running keeps me warm and lets me move over snow and ice without slipping too much — did you know it’s easier to run on ice than to walk on it? I like the sense of accomplishment I feel for even making it out the door on a bleak winter day, the longer distances (than walking) I can travel, what the speed and effort of running does to how I pay attention, and what I pay attention to, how it feels to effortlessly glide over ice or to slide and shuffle over gritty snow, the sense of solitude, and the sense of community with others who have also made it outside.

In “The Magic of Winter Running,” Jonathan Beverly describes running in Chicago during a snowstorm:

Out on the lakeshore path, the snow swirled around me, softening the hard lines of the city that emerged and disappeared as I floated along in a snow globe. I ended up doing 8 miles, feeling no fatigue, high-fiving the other crazies out running, all wearing the same huge, idiotic smile I could feel on my face (The Magic of Winter Running).

And Thomas Gardner writes about one of his winter run:

Sunday morning—23 degrees, both ponds frozen and glassy. Six miles. About an inch of ice on the trail—frozen snow-melt, frozen slush—but I managed to stay upright. Spent the run thinking about texture, most of the ice hollowed out from below or mixed with leaves or raised up in welts, with just enough give for me to run at a decent pace, thinking with my feet. Some patches of glare ice, dusted with snow, where I’d pick my way lightly, or slide by in the leaves on the side (December 30, 2012 / Poverty Creek Journal).

Biking:

On the Mississippi River Gorge Trail, I encounter bikers all winter. I imagine some of them are commuting to work, while others are probably out enjoying the chance to move and breathe and see the grayish-white emptiness of the river. Often these bikers ride bikes with heavy frames and extra thick tires: Fat tires. I always make note of the fat tires I see. Maybe you ride a fat tire? I don’t, but I bet it’s a wonderful way to notice the world outside in winter! If, as Gardner suggested in the passage above, that running is about thinking with your feet, biking must be about thinking with your tires!

One day, running by a house I love because they post poems on their front windows, I encountered this winter biking poem:

Maybe Alone On My Bike/ William Stafford

I listen, and the mountain lakes

hear snowflakes come on those winter wings

only the owls are awake to see,

their radar gaze and furred ears

alert. In that stillness a meaning shakes;

And I have thought (maybe alone

on my bike, quaintly on a cold

evening pedaling home), Think!–

the splendor of our life, its current unknown

as those mountains, the scene no one sees.

O citizens of our great amnesty:

we might have died. We live. Marvels

coast by, great veers and swoops of air

so bright the lamps waver in tears,

and I hear in the chain a chuckle I like to hear.

The stillness! The solitude! The marvels we coast by! The swoops of air! And, that chuckling chain!

Sledding

When my kids were much younger, I would take them sledding, and what I remember noticing were the textures, feeling the ground, understanding/reading the snow in new ways — not by how pretty it looks, but by how fast it might speed me down the hill, or how hard it might feel on my tailbone as I flew over a deep dip.

I was born in the north, in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan with ridiculous amounts of snow, but I grew up in the south — North Carolina and southern Virginia — where even flurries meant early dismissal from school. Maybe that’s why I like this poem about sledding in Wichita; it reminds me of being a kid and finding joy on a small scale.

Sledding in Wichita/ Casey Pycior (pee chore)

As cars pass, laboring through the slush,

a boy, bundled against the stiff wind

in his snow suit, gloves, and scarf,

leans on his upright toboggan,

waiting his turn atop

the snow-packed overpass—

the highest point in town.

First one car exits, and then another,

each creeping down the icy ramp.

The brown grass pokes through

the two grooves carved in the short hill.

As the second car fishtails to a stop at the bottom,

brake lights glowing on the dirty snow,

the boy’s turn comes.

His trip to the bottom is swift—

only a second or two—

and he bails out just before the curb.

It’s not much, but it’s sledding in Wichita.

These winter words, especially the line, The brown grass pokes through/the two grooves carved in the short hill, conjures a childhood of settling for subpar snow and hardly hills. I suppose one of the reasons I love snow is because it was so rare when I was a kid. I know that’s why I love spotting a cross-country skier on the river road trail. I never saw anyone skiing until I moved to Minnesota in my 20s!

Cross-country Skiing:

Speaking of cross-country skiing, it’s another great way to move and stay warm while getting outside in the winter. In the article, “Winter Wellness: Forest Bathing on Skis,” Hannah Fries describes a winter afternoon out on her skis:

The shhhh shhhh shhhh of my skis, the click of my poles, the wind, and my own breathing are all I hear. When I stop, it’s just the soft ticking of snow on my jacket. Everything is white and gray and sepia, blurred by the fast-falling flakes.

As I ski along the farthest edge of the field — where, from a distance, I often see deer or coyote standing with ears perked — I scan the ground for tracks. But there’s only this fresh sweep of snow, no sign that any warm body has been here today at all. As I head home, fingers warm now, breath steady, a quick wingbeat flutters some twenty feet above my head: the signature flap, dip, and glide pattern of a woodpecker.

Finally, Shoveling:

At my house, I am the resident shoveler. Mostly by choice. It’s a chance to get outside on a cold day, to check out how much snow had fallen, to feel the satisfaction of clearing a deck and some sidewalks. As I shovel, I like hearing the chatter of the birds, the buzz of others’ snowblowers cutting through the quiet, an occasional neighbor calling out a greeting across the alley.

Drift/ Alicia Mountain

The gold March dawn

and below my window

a man carves his car

from the snow heap

plowed up around it.

So easy not to envy

the cold muscled task

but then imagine—

feeling your heartbeat

alive like a chipmunk

at work in your chest,

imagine the whole day

arm-sore and good

with accomplishment,

the day you begin

with heavy breath

and see it linger

outside your body

like a negative of

the dark air cavityin you like the spirit

in you like the ghost.

I appreciate what Mountain writes in her description of it:

This poem is an exercise in re-encountering the familiar. Lately, I’ve been trying to take another look—at poem drafts, at circumstances, at assumption, chores, beliefs. More and more, I have come to understand myself as a draft of a person to which I return and try to see again, anew.

Some other winter chores that you might consider using for your movement logs: scraping the ice and snow off your car, kicking the chunks of snow out of your wheel wells, taking the trash out in the dark, under the stars.

question: what types of winter movement will you try?

Translating Attention and Wonder Into Words, part one

Each week, I’ll offer up a suggestion for how to translate your attention and wonder into words. For this week, it’s an exercise I like to use in many of my log entries: 10 Things I Noticed.

Making a list of 10 things you noticed to include in your movement log entry is a great way to get in the habit of noticing, and then remembering what you noticed. I like making it 10 because that amount of things is more of an effort to remember or keep track of than 5 or 6. This extra effort can lead to unexpected memories. Sitting down with my log, I often wonder how I’ll come up with as many as 10 things, but I usually do. And the act of finding those things, somewhere in my memory after my run, becomes part of the process, helping me to tap deeper into my passive attention (those thing I noticed without realizing I noticed).

This exercise can be basic or have (almost) endless variations, like 10 things I heard, 10 things related to water, 10 things: wheels, 10 smells, 10 things that flew in my face, 10 colors, 10 strange characters encountered, etc.

You can compose the list after you move, or in your head as you move, or by stopping every couple of minutes or blocks during your moving to add something to a list you carry with you on a piece of paper or that you’ve created on a voice memo on your phone.

When trying it out in this first week, start simple. After you move, list 10 things you noticed while moving outside in a log entry. We will keep experimenting with this exercise throughout the six weeks.

With each list item, focus on describing the thing itself. No abstractions, interpretations, or metaphors. Here’s an example from the poet Marie Howe: “Just tell me what you saw this morning like in two lines. You know I saw a water glass on a brown tablecloth. Uh, and the light came through it in three places.”

Something to Think About as You Move

For this first week’s readings, I’ve selected a few brief passages on the value of moving, the importance of practice, and the wonder of winter from runners, walkers, poets, and a nature writer. As you move this week, try thinking about these passages. Did any of them change or reinforce your experiences moving outside. Do any of the passages stand out for you — that you especially liked? Disliked? Also, were you able to hold onto your thoughts about them as you moved?

This class is about developing a practice of noticing by moving outside. I’ve talked about the value of moving, and being outside. I’d like to end by encouraging you to think about your body as a key part of this practice — this is a full body practice, about not just noticing the world, but noticing your body moving through it. What might this do to how you notice, what you’re in wonder of, and how you translate that wonder into words?

For the rest of your walk or run today, I’d like to leave you with lines from the poet, Edward Hirsch and the philosopher, Frederic Gros:

from Hirsch:

A walk is a way of entering the body, and also of leaving it.

from Gros:

You are nobody to the hills or the thick boughs heavy with greenery. You are no longer a role, or a status, not even an individual, but a body, a body that feels sharp stones on the paths, the caress of long grass and the freshness of the wind.

Questions:

How do you enter your body while moving? How do you leave it?

What does your body feel as you’re moving through a place?