Wonder as Curiosity

It starts with astonishment, then you want to know more: What is it? How does it work? What stories does it tell? Why is it so astonishing? Now you’re not just in wonder of the world, but you wonder about it. You are curious.

To be curious about the world is to be interested in it, to give attention to it. To admit you are not an expert who knows everything, but a beginner, who wants to learn new things, or learn old things in new ways. To see the familiar as strange and explore its mysteries. To look to others for help in understanding. To ask questions, imagine possible answers, generate more questions. To want to learn more, but also be willing to let go of a need to know everything. To stay for a while in a space of uncertainty and see what happens.

Lucille Clifton describes this willingness to stay in a space of uncertainty as the foundation for poetry: “it’s not about [answers], it’s about questions. So you come to poetry not out of what you know but out of what you wonder. And everyone wonders something differently and at different times.”

Mary Oliver suggests it could be a life goal: “Still, what I want in my life is to be willing to be dazzled – to cast aside the weight of facts and maybe even to float a little above this difficult world. I want to believe I am looking into the white fire of a great mystery.”

And, Aimee Nezhukumatathil (neh-ZOO / KOO-mah / tah-TILL) argues that it offers a way for us to connect with the world and each other: “What if we wrote about what we wondered, no matter our age or our education? What if we allowed ourselves to admit we don’t have all the answers, that we depend on someone else’s experience and knowledge? A humbling of ourselves. What if we shared the abundance of what we wondered about, what we’re curious about? This reminds us that we’re all interconnected. We need each other to help us grow in our understanding of each other. Because when you make wonder a habit, you feel less alone.”

question: What do you wonder about?

Being outside and in motion is an excellent chance to be curious about the world. Moving opens us up and makes us more able to wander with our thoughts, to be creative, imaginative, willing to explore all sorts of answers without settling on just one. While we’re moving, it’s harder to look things up and find “the ANSWER” — if one answer is even possible, or if the answer you find online is accurate or trustworthy. Instead, we can remain in a state of mystery and possibility. And, when you’re outside, even if it’s a space you regularly move through, there’s so much to wonder about! So many strange and marvelous things happening! So many stories we haven’t yet heard! So many ways to connect with the world!

Almost every time I go out for a run or a walk on the trail that I’ve traveled on for thousands of miles, I come up with new questions about the river, or the birds, the trees, the histories of the land, the people who frequent the trails, the sounds, the smells, the textures. Here’s a list of a few of them:

List: 10 Things I’ve Wondered About While Running Beside the Gorge

- Why is it so quiet in the winter? Why is it so loud?

- Why (and how) is this tree growing through that fence? What is that process called? How old is this tree and that fence?

- What are the different layers of rock in the gorge?

- Why do some geese stay here all winter? Why do they honk, and why are their honks so harsh and exciting?

- Why did this tree fall? How loud was the crack when it hit the ground? Did they hear it across the neighborhood? When will Minneapolis Parks remove it?

- Where do the turkeys go when it’s 20 below?

- Why do some trees have holes that look like eyes, and what are those eyes called?

- How did the Mississippi River Gorge become part of the National Park System?

- Why is it that when I see one glove, forgotten on the trail, it’s always black?

- Was that sound a chainsaw, a snow blower, a vacuum, or something else?

I’ve written about these questions in my running log. Some of them appear in only one log entry, others I return to again and again for several days or months, or even years. All of them are part of what the runner/teacher/poet Thomas Gardner describes as an ongoing conversation with the landscape and myself. This ongoing conversation has enabled me to develop a relationship with/to a place. To learn more about it, and to learn from it.

Sometimes my curiosity is about finding specific answers and sometimes it’s just about gesturing towards other possibilities. Always, it’s about opening the door to attention in order both to learn from the world and connect to it. Here are 3 different ways I practice my curiosity when I’m moving and outside:

one: When I’m curious about something I’ve encountered, I try looking it up online after I return from moving outside. The internet gets a lot of well-deserved criticism, but it isn’t all bad — it isn’t all distraction or misinformation or the only reason we feel disconnected or alone. There’s an abundance of sites that can help fuel and sharpen your curiosity. Online journals with amazing lyric essays about rocks or fossils or fungi (some of my recent interests). Regional Park sites that can help you figure out the difference between a brook, a stream, a creek, and a river. And online education centers that can help you identify that 2 note birdsong that you’ve been hearing forever. These sites can lead to more wonder and better questions.

two: I spend some time speculating, then I return to the place/the thing that the question is about and try to find an answer. Here’s a recent example. Reading up on the north entrance of the Winchell Trail, which I run above on my regular route, I read something that mentioned a boulder with a plaque dedicated to the geologist Newton Horace Winchell near that entrance. But, where was this plaque? The article seemed vague and I had never noticed a plaque in my hundred (or more?) runs near this trail. In my next run, I searched for it, and there it was, right before you reach the Franklin Bridge. How many times had I run past this plaque and ignored it? Now I notice it (almost) every time. And, I’ve started to notice more of the signs and markers and info kiosks that tell some of the history of the place I run through.

three: Not all of my wondering involves specific questions to be answered. Sometimes I notice something and wonder how others have noticed this same thing and written about it. I like to look the wonder up on a poetry site, like Poetry Foundation or Poems.com, and find a poem that features it. After reading the poem several times, and making note of words and images I especially like, I post it as part of my log entry. This practice has become such a habit that it’s a regular feature of my log. I return to these poems to reread them and do fun poetry experiments with them.

Translating Attention and Wonder into Words, parts four and five: condensing (4) and finding new ways in (5).

In the first three suggestions for translating wonder into words, I focused on things you could add to your entries: a list of 10 things you noticed, your route, the weather. For parts 4 and 5, I’ll discuss ways to play around with words and use certain limitations to help you condense your observations/reflections (4) and to open them up to new meanings (5).

First, condensing with the minison (mini sonnet):

Some time after you have written your log entry, read through it again. Pick some details and try to summarize them using the limits of a new poetic form I just found, the minison: 14 letters OR 14 words.

As the creators of the form write on their site, the only “rule” is 14 letters. Achieving it in 14 words is a variation by the poet Seymour Mayne. The point of this experiment is not to craft a perfect poem, but to give more attention to your words as you try to figure out how to make meaning with only 14 letters or 14 words. It’s also to have fun.

I tried this out with my January log entries and enjoyed it. Many of my minisons — I created both 14 letter and 14 word versions — are not brilliant, but a few of them are promising, and most of them offer a helpful and pithy summary. All of them allowed me to spend more time with my attention and wonder about the place I had just moved through.

The

paved

path

was

almost

all

lake

with

a

side

strip

of

sheer

ice.

jan 27: my body as tether, I talk to the wind, a knee says hello

Poets love to experiment with limits. Instead of the minison and limiting your letters/words, you could condense your entries with syllable restrictions, like

the haiku: 17 syllables (lines of 5/7/5)

the tanka: 31 syllables (lines of 5/7/5/7/7)

the lune: 11 syllables (lines of 3/5/3)

Second, finding new ways in with acrostics, abecedarians, and alliteration:

Turn part (or all) of your entry into an acrostic poem by picking one of the things you noticed and were in wonder of/wondered about and writing it vertically down the page. Each letter of your wonder becomes the first letter of a line in your poem. While this type of poem is often used in elementary school, it’s not only for kids. It can be fun and if you’re intimidated by poetry or are having writer’s block, it’s a wonderful way into more words!

Turn your entry into an abecedarian poem. Each line of the poem begins with a letter of the alphabet. You can start with a and end with z, or start with z and end with a. Variations to try: Find and list things you noticed or experienced as you moved for each letter of the alphabet. Or, be more specific: list 26 (a-z) forms of snow/ways to describe snow/textures of snow, etc.

Use alliteration. Read your entry and pick out a letter that you used most often. Make a list of words related to the place you moved through that start with that letter. Edit your entry to feature that letter. Do not use a dictionary when creating your list, try to think up the words on your own. Here’s an example from October 30, 2019:

Ran north on the river road until I reached the bottom of the franklin hill. Reversed direction, running back up the hill. Took a set of wooden stairs down to the rusty red leaf-covered Winchell Trail. With reluctance, resorted to walking most of it–too risky to run…so many hidden roots and rocks and ruts! As I carefully hiked the steep rim, more and more of the railroad trestle revealed itself. I’ve never approached it from this angle. Returned to the paved path by the road after climbing another set of stairs right by the rickety, rotting split rail fence. Listened to the sounds around me. Rusty, rustling leaves, rooting rodents. What a racket! Ended my run by the 2 big rocks. Before leaving the river, remembered to stop at the overlook and then the ravine to absorb the roomy view.

Week Four Reading Passages

This week’s readings are from four different poets: J. Drew Lanham (Sparrow Envy), Paige Lewis (Space Struck), Heather Christle (The Crying Book), and Aimee Nezhukumatathil (World of Wonders).

In addition to being a poet, J. Drew Lanham is an ornithologist who often writes about being a Black American birdwatcher (9 New Revelations for the Black American birdwatcher). As I pay attention while running by the gorge, I often try to take his advice and be with thebird.

I picked the second passage, which comes from an interview with Paige Lewis for the poetry podcast VS., because I appreciate Lewis’ enthusiasm for noticing and their wonder about tiny beautiful things.

The third selection is a poem, “What Big Eyes You Have,” from Heather Christle. I love this poem and the connections it makes between curiosity, wonder, and being a kid. I also like how it offers a counter to scientific curiosity which is exemplified in a passage from Henry David Thoreau that I came across while prepping for this class:

In winter, nature is a cabinet of curiosities, full of dried specimens, in their natural order and position.

Instead of a cabinet of curiosities holding individual specimens, what if we imagined our curiosity and things we collect as a crafts/junk drawer — nothing thrown away and everything mixed together?

The fourth selection is from poet and nature writer, Aimee Nezhukumatathil. She’s written a book all about her favorite wonders in the natural world. I’ve included a chapter from her book in the Additional Resources section.

The passage of hers I selected comes from a “Poetry off the shelf” podcast episode about Walt Whitman, the climate crisis, and the joy of excessive enthusiasm (or, as she describes it in the interview, “having no chill”).

Nezhukumatatil’s idea of being in wonder and wondering as contagious, brings us to my second installment of winter wonders. This week, I’ll talk about snow.

Wonder Two: Snow!

Living in Minnesota, it’s hard to think about winter without thinking about snow. So much snow, often starting in October and not ending until April, occasionally May. 2023 is no exception. As I write this, it’s early February and we already have more than 4 feet of snow — 52 inches! I wonder, by the time you’re reading or listening to this in mid-February, how much snow will we have? As a kid living in North Carolina and Virginia, the rare snow day was exciting, improbable, delightful. Now as an adult, growing older in Minneapolis, snow is almost always here, often accumulating in slow steady inches overnight. Dusting after dusting, only to be discovered when I go downstairs in the morning, open the curtains, and exclaim, What?! More snow? More snow to be shoveled, plowed, removed, navigated.

Even in its excess, I love snow and find it a constant source of curiosity. Definitely not always a delight, but endlessly interesting, more than mundane, something to notice, to wonder about, to be with in so many ways.

On February 1, 2018 I wrote in my notebook:

Spend less time looking down at the gorge, more time focusing on the path. Looking for loose chunks of snow — deceptive mounds that seem soft but aren’t. Ready to twist an ankle, break a toe.

With this suggestion to myself, I began an ongoing conversation with snow and the running path. Initially this conversation was practical, motivated by my failing vision and the need to look more carefully for obstacles, but it grew into much more as I gave my attention to studying my neighborhood sidewalks and the paved trail that follows the river. I searched for answers to the questions: what does the path feel like? sound like? look like? Rather quickly, these questions led to a deeper curiosity about snow and what the snow felt and sounded like, mostly after it had fallen and was on the path.

On February 9th, I wrote in my online movement log:

Been thinking a lot about snow, snow-covered paths, the noises snow makes and why snow sometimes looks blue. I read the poet Su Smallen’s Kinds of Snow and did some research on snow squeaks. I’m collecting lots of snow words that I hope to use in a poem: snow grains, snow pack, dendrites, hoarfrost, watermelon snow, compacted, trodden, the blue hour, crystals, needles, flakes, graupels, sintering, collapsing, compressing.

For the next month, I collected versions of the snow and many words related to snow. And I spent time with two of its sounds — noticing, recording, and listening to them, exploring the questions they posed for me, fitting them into poetic forms.

Collecting Versions

Here are some versions of the snow that I started collecting in Feb of 2018, and have added to in later winters:

First snow, last snow, unending snow, an epic snow that shuts down the city and has people cross-country skiing in the streets, a promised snow that never arrives. Snow that sticks, slips, stays, that falls but never lands. Slick, quiet, loud, heavy, wet, dry snow. Powdery, thick, clumped, the texture and color of sand snow. Snow that’s fun for sledding, good for snowballs and forts, easy to shovel. Snow that starts white then turns blue, brown, gray, black. Snow piled so high that it blocks the escape of a frantic mouse or puddles turning the path into a lake. Snow that melts in the morning, then freezes again in the evening. Soft snow that falls gently on my shoulder. Sharp snow that stabs my cheeks. Snow that falls straight down, off to the side, all around, that stops momentarily when I pass under a bridge. Freshly fallen snow that gathers in the corners, on the edges, only on one side of a tree. Stale snow that hardens, accumulates, collects in wheel wells, narrows already narrow streets. Snow that absorbs sound or amplifies it. That dulls or dazzles. That conceals or reveals.

Collecting Words

So many words to discover or create that are related to snow. Part of my curiosity about snow involves exploring how poets write about it. Here are three of of my favorites:

one: Snow-flakes/ Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. A few years ago, I memorized this poem. Sometimes I recite it in my head as I run when the snow if falling.

Snow-flakes/ Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Out of the bosom of the Air,

Out of the cloud-folds of her garments shaken,

Over the woodlands brown and bare,

Over the harvest-fields forsaken,

Silent, and soft, and slow

Descends the snow.

Even as our cloudy fancies take

Suddenly shape in some divine expression,

Even as the troubled heart doth make

In the white countenance confession,

The troubled sky reveals

The grief it feels.

This is the poem of the air,

Slowly in silent syllables recorded;

This is the secret of despair,

Long in its cloudy bosom hoarded,

Now whispered and revealed

To wood and field.

One of my favorite parts: “This is the poem of the air,/slowly in silent syllables recorded”

two: After the Snow/ Linda Pastan (from Insomnia). I discovered this poem a few days ago, shortly after Pastan’s death at the age of 90. It speaks to the way snow can transport us to other places.

After the Snow/ Linda Pastan

I’m inside

a Japanese woodcut,

snow defining

every surface:

shadows

of tree limbs

like pages

of inked calligraphy,

one sparrow,

high on a branch,

brief as

a haiku.

Here

in the Maryland woods, far

from Kyoto

I enter Kyoto.

question: Does snow transport you to other times or places?

three: A Blank White Page/ Francisco X. Alarcón. I think I found this poem a few years ago after typing “snow” in the search bar on the Poetry Foundation site. I like the connection between the blank space of a page with the blank white field snow creates.

A Blank White Page/ Francisco X. Alarcón

is a meadow

after a snowfall

that a poem

hopes to cross

Collecting Sounds

Early on in my conversation with snow, I noticed a sound — well, 2 sounds — that irritated and delighted me, then made me curious about why they delighted me and how they were made: crunching snow. I listened for them, recorded them with my phone, researched why they happened, then experimented with writing poetry about them.

On February 2, I wrote in my log: I ended my run at 4 miles, right by the welcoming oaks. Walking, I began to notice how my left and right foot each provided a slightly different crunching sound. I liked it so much, I had to record the sound:

On February 7: Glad I didn’t wear any headphones because I got to hear the snow crunching. Two sounds. One that was steady, almost like grinding or styrofoam being crushed. The other that was softer and shorter. I like these sounds, maybe partly because they are a little annoying.

February 14: As I was walking and listening to the sounds, I started thinking about the many different ways a path can crunch: shattering snow crystals, friction from dry snow grains rubbing against each other and/or my foot, salt or sand scratching on the pavement, the treads of my shoes loaded with little pebbles scuffing against the ground.

February 20: 2 distinct sounds. One, a steady grinding, like gears with small teeth turning rhythmically, constantly, the other, one quick thrust, like a small shovel being thrust into sand or small pebbles. I think that the sounds trade off between my moving feet. But how? I need to go out and walk in the snow some more to figure it out!

February 21: Crunchy path. I was struck by how the 2 crunching sounds of my feet highlighted the differences between walking and running. When I was walking, the slower, steadier crunch lasted longer, as my foot went from the initial heel strike to the final toe-off. How many bones came into contact with the crunchy snow? When I was running, that second crunch was quicker, with less grinding. I’d like to capture some sound of me running on crunching snow, but that seems hard.

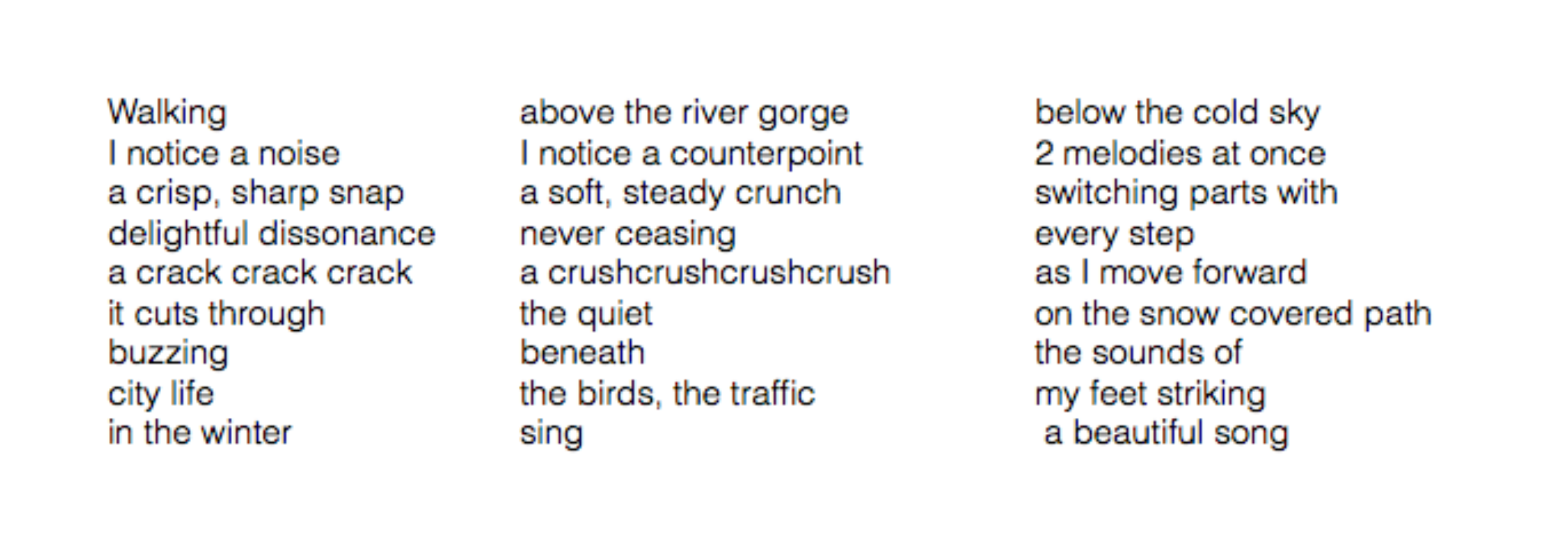

3 poetic forms about crunching sounds: acrostic, homage, contrapuntal

As I listened to and studied the 2 sounds of crunching snow, I experimented with poetic forms for expressing my wonder. I wrote an acrostic about the magic of these sounds that spelled out the word, Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response (ASMR). I wrote an homage poem based on Alice Oswald’s poem, “A Short Story of Falling,” about how the snow transforms after it has fallen called “A Short Story of Fallen Snow.” Then, a few months later, I wrote a contrapuntal poem in which I put 3 distinct poems, two about the crunching snow sounds and one about their combined song, together. I titled this one, “The Biomechanics of a Step, Amplified.” Here are my notes about that poem from a log entry dated April 8th, 2018:

First, I noticed the noise: a crisp, sharp, snap. Delightfully dissonant, cutting through the quiet and the soft settling of my foot on the snow-covered path. Did I like it partly for its grating, grinding quality?

Then, I noticed its counterpoint: a soft, steady crush of crystals that never ceased. Sometimes creaking, occasionally squeaking. Always there, buzzing, humming under the other noises—birds chirping, planes rumbling, a car door slamming.

Before I had only made note of the noise and how it shattered my idea of snow as silent. Now I wondered how the different noises fit together. Why two? What was causing the multiple melodies? The crack crack crack with the crushcrushcrushcrushcrush?

Then, I understood. The two sounds traveled, trading off between my feet. As one foot cracked, the other crushed. Right crack left crushcrushcrush left crack right crushcrushcruch. The biomechanics of a step amplified! My body singing through snow!

Here is the sound:

And here is the poem:

The Biomechanics of a Step Amplified, Contrapuntal

Something to think about as you move: birds in the winter

One thing that is almost always an astonishment for me in the winter, when it’s below 0: the birds and their birdsong. Some birds leave in late fall, but there are plenty that stay through the winter, including: the pileated woodpecker (which many of us have mentioned), the blue jay, and the black-capped chickadee. In Winter, Dallas Sharp Lore writes of the chickadee:

It is worth having a winter, just to meet a chickadee in the empty woods and hear him call — a little pin-point of live sound, an undaunted, unnumbed voice interrupting the thick jargon of the winter to tell you that all this bluster and blow and biting cold can’t get at the heart of a bird that must weight, all told, with all his winter feathers on, fully — an ounce or two!

As you move outside on a cold day in winter, be with the birds. Listen for their songs, look for the flurry of their feathers, sense the shadow of their flight.