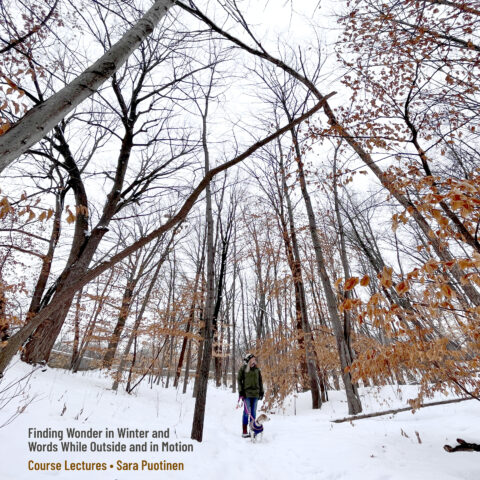

Welcome to Finding Wonder in the World and the Words While Outside and in Motion! My name is Sara Puotinen. I live in South Minneapolis, 4 blocks from the Mississippi River Gorge. Over five years ago, I began a project that combined my research and writing in ethics and storytelling with my growing interest in poetry and my strong desire to reconnect with both my body and the place I live in. Well, it didn’t start quite like that — my project began as a blog about running and the experience of training for my first marathon. After I took an experimental poetry class at the Loft, it began to change: more poetry and more experiments with searching for better words to describe what it feels like to be running beside the gorge. Then, when I was injured and unable to do the marathon, it grew beyond documenting my running to exploring what it means to be moving while writing and writing while moving, and how both help me to notice a place, the Mississippi River Gorge, and be in wonder of it. This class comes out of this ongoing project and is built on ideas and experiments I’ve been working on since 2017. I’m so excited to share these ideas and experiments with you and see what happens!

Transcript continued

My project began as something fairly simple: train for a marathon and write about. As it grew, I took on many more goals: learning to notice, to slow down, to find delight; searching for better words for describing what I think about when I’m running, how I experience that dreamy state mid-motion; building skills to help me navigate the world as I lose my central vision; devoting more attention to poetry; and finding ways to endure the pandemic. I don’t approach any of my goals directly, but wander between them, experimenting with new ways to build on them. It’s messy and exuberant, and what makes it work is the structure and discipline of my small, steady practice: I go outside and move. While I’m moving, I try to pay attention. Then, I return home and write about it. I play around with this habit in many different ways, but the basic structure stays the same. This structure helps tether me to the world and to a larger purpose and intent. This class is designed to give you a chance to try out this basic structure and see how it might work for you.

To establish this structure, we’re building off of Mary Oliver’s suggestion in her poem “Sometimes.” She writes:

Instructions for Living a Life:

Pay Attention.

Be Astonished.

Tell About It.

For this 6 week class, our version of Oliver’s instructions will be:

Go outside, move.

Pay attention while moving.

Be open to wonder.

Write about it in a movement log.

Each week we’ll focus on a different aspect of these instructions, all while working to establish a practice of being outside and moving on a regular basis. Week one will be about the value of going outside and moving. Week two, attention. Weeks three and four, wonder as delight and curiosity. Weeks five and six, translating wonder into words that move and breathe.

Three elements that are central to this class are: 1. moving through an outside space, 2. developing a habit, a ritual, a practice and 3. using a movement log both to document that practice and as part of the practice.

Moving through outside space

There are many ways in which standing or sitting still outdoors somewhere can help with paying attention and being in wonder. And, moving, then briefly stopping, will be part of some of the experiments you can try. But, for this class, we will focus on moving through outside space and the specific ways it helps us to notice the world and be in wonderment of it — what moving does: to how we think or feel or notice; to words, ideas, our connections to a place; to us, our understandings of self, our breathing, our senses. In moving, it might start with the physical, “the heart pumping faster, circulating more blood and oxygen not just to the muscles but to all the organs—including the brain,” but something beyond the physical often happens: we feel different, more open to the world, more willing to notice and be with it. Moving through outside space is important too. Hopefully it enables us to breathe fresh air and to be out in the world. It also gives us the opportunity to devote time and attention to a place, not only to become more familiar with it — its histories, terrains, inhabitants, but to behold it and care for and about it, to imbue it with more meaning and make it sacred.

Developing a practice

Learning to give attention and be open to, and then in wonderment of, the world are things we need to practice repeatedly. For many of us, it was easier when we were kids and full of curiosity. As adults, it’s harder to slow down, to notice the world and be dazzled by it. We don’t have time. Our attention spans have shortened. We’re discouraged from expressing too much enthusiasm. We’ve been overwhelmed by life — too many obligations, too much suffering. We need to remember and re-learn how to pay attention and be moved — astonished, dazzled, amazed — by what we notice. One way to do this is through practice: dedicated effort on a regular basis. And one way to do this practice is by going outside several times a week and moving, then writing about it, either after returning home or while still outside.

Using a movement log

While outside and in motion, even when we notice things and are in wonderment of them, it’s easy to forget what we noticed, or how we felt while noticing it. A movement log is a great way to document this. Not only does it give you a record that future versions of yourself can look to (I’m constantly thanking past Sara for what she wrote down that I would have otherwise forgotten), but the act of writing it down — sitting somewhere and remembering, thinking through your time outside and putting it into words — becomes part of the practice of giving attention and being in wonder.

Movement logs can take many forms. Mine is a blog, but you could write in a notebook or a word document, make a video, record yourself speaking the details, or whatever else you want to use. It’s up to you. The point is to do it, to create a regular space and time for writing down what you noticed/felt/thought as you moved.

The practice of paying attention, being in wonder, and writing about it, doesn’t have to be overwhelming, or take too much time. For this class, our outdoor experiments will be aimed at 45-60 minutes, at least 3 times a week — 30 minutes of moving outside and 15-30 minutes of writing about it. And, there won’t be too many rules for how to do it. There will be suggestions for what you can do, but you decide how to create and build your own practice.

The overall goal of this class is to give you the time and space to experiment with a new practice of paying attention while moving outside. Some things might work, others might not. This is your opportunity to have fun, to experiment, to share strategies and be inspired by others in the class, and to be outside and moving during the summer.

Don’t worry that what you notice isn’t important, or that how you write isn’t smart enough. Everything is worthy of attention. Anything can be a source of delight. And you never know when or how the words you write will open doors to new understandings and new worlds — for you or for anyone who reads your words.

As Mary Oliver suggests in her poem, “Praying”:

It doesn’t have to be

the blue iris, it could be

weeds in a vacant lot, or a few

small stones; just

pay attention, then patch

a few words together and don’t try

to make them elaborate, this isn’t

a contest but the doorway

into thanks, and a silence in which

another voice may speak.

The value of being outside and in motion

Stepping away from a desk, getting up from a chair, heading out to a trail, can help us untangle knots in our thoughts, work through difficult ideas, find better words. It can open us up, slow us down, transform our thinking, enable us to get to know a place, inspire us, providing details, images, experiences for our work. And, it can make what we write move and breathe.

I love this quote from the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche in his book, The Gay Science:

We do not belong to those who have ideas only among books, when stimulated by books. It is our habit to think outdoors—when walking, leaping, climbing, dancing, preferably on lonely mountains or near the sea where even the trails become thoughtful. Our first questions about the value of a book, of a human being, or a musical composition are: Can they walk? Even more, can they dance?

Being outside and moving is not limited to one type of movement or one type of place. For example, it could be swimming or biking. It could be the woods or a busy city street or a suburban bike trail. For this class, I’ll emphasize running and walking in park spaces, but there’s room to think about moving outside in other ways, which could be fun to imagine and experiment with. For example: as an open water swimmer, I’m fascinated by what moving through lake water does to my senses and how and what I think about.

Here are a few reasons I’ve come up with for why

Moving outside is magical:

- Fresh air! Open spaces! More room to breathe and to be!

- You use your body and work on your relationship with it, find new ways to make it part of your writing

- Gets you up, out of your chair

- Clears your head, restores your mind, unclenches your jaw

- Encourages more casual, relaxed thinking, attention that slowly wanders from here to there instead of quickly darts from this to this to this

- You get to hear some birds or dogs or roller skier’s poles clicking and clacking

- A chance to encounter something delightful or ridiculous or strange, to collect a new image or story, to experiment, to be with the river

- Sometimes you lose yourself

- Sometimes you find yourself

- Learn more about your neighborhood — the people or the dogs or the terrain

- Helps you work through a problem — in your writing, life

- Helps you forget some things, remember others

- Revelations, the runner’s high, reverie

- The possibility of syncing your brain with your feet and the world

- Developing a practice that opens you up, enables you to find better words, and gets you through the early stages of the pandemic

Read more about what some other writers think about the value of walking and running by checking out the selected passages for week one — Reading: Passages.

Something to Think About as You Move

For the rest of your walk or run today, I’d like to leave you with a few other brief passages from 2 writers, Edward Hirsch and Frederic Gros:

from Hirsch:

A walk is a way of entering the body, and also of leaving it.

Wandering, reading, writing–these three adventures are for me intimately linked. They are all ways of observing both the inner and outer weather, of being carried away, of getting lost and returning.

from Gros:

You are nobody to the hills or the thick boughs heavy with greenery. You are no longer a role, or a status, not even an individual, but a body, a body that feels sharp stones on the paths, the caress of long grass and the freshness of the wind (84).

Questions:

How/what does your body feel as you’re moving through a place?

What is your inner and outer weather?